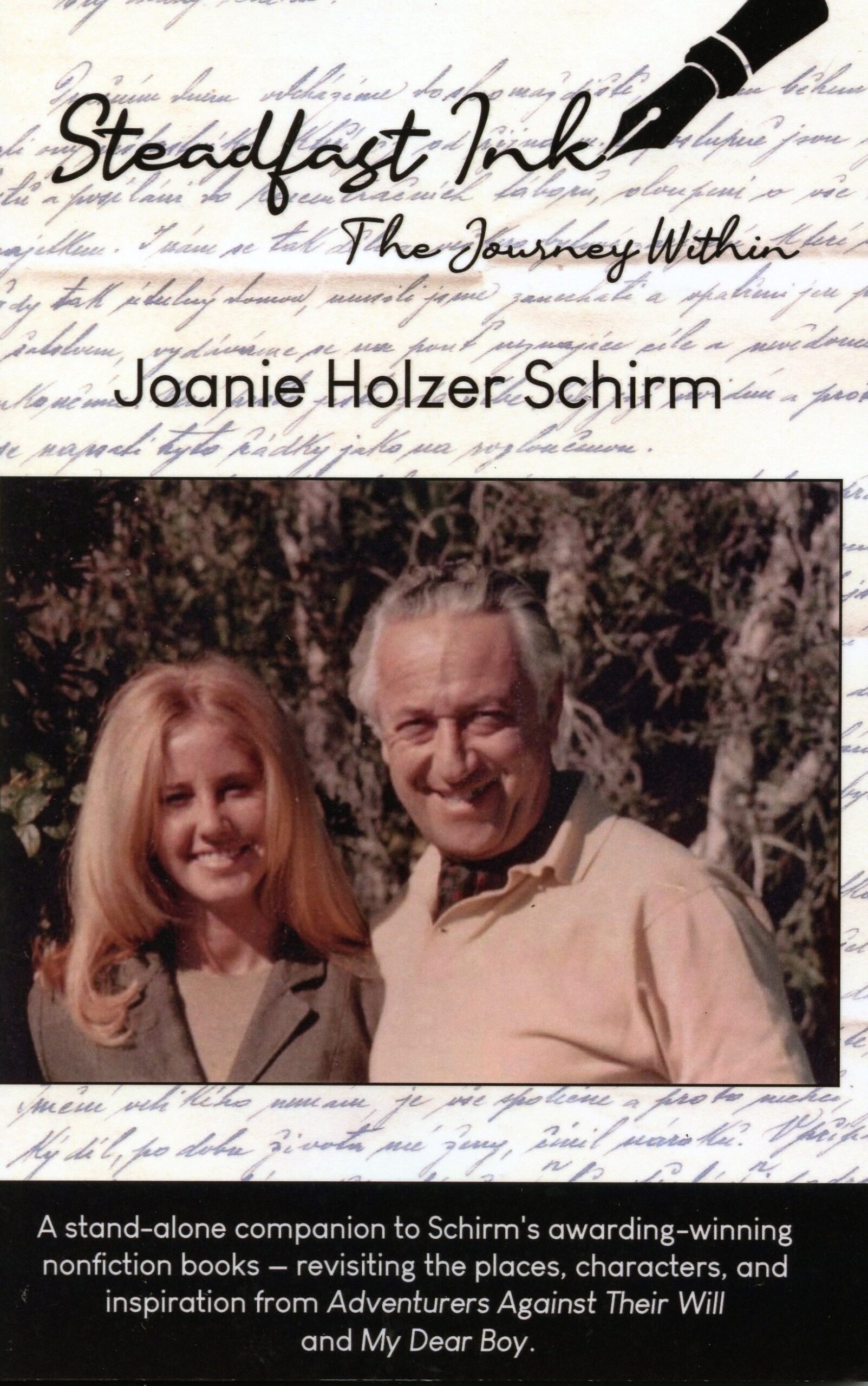

Part 2 in the Series

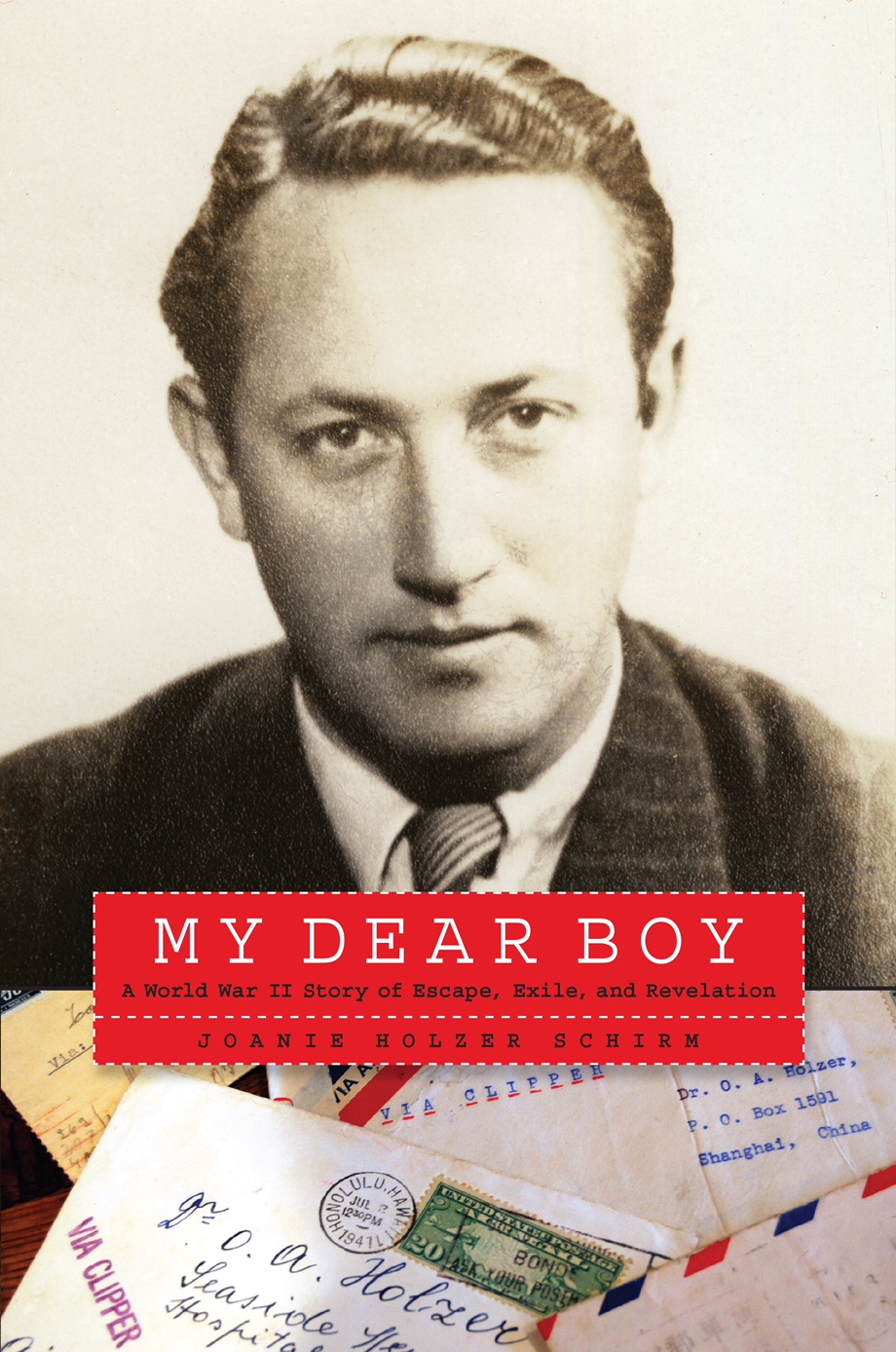

As the years slipped away during the writing of My Dear Boy, one thing became crystal clear. My journey of research and writing was dramatically enhanced by the people who often serendipitously came aboard for the ride and then remained my friends to the journey’s end.

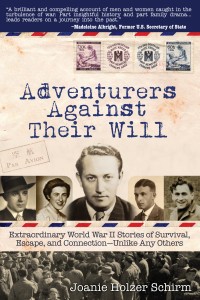

What follows in this Part II, is an introduction to Tom Weiss, number two of the key individuals who helped set free the seventy-eight voices of the four hundred World War II letters my beloved father, Oswald “Valdik” Holzer, hid away after the war. Translators, experts, travel guides, administrators, archivists, and more, each with full heart, played an indelible role.

Tom Weiss

Before the age of sixty, Tom (Fischer) Weiss of Newton, Massachusetts, had little interest in his family history. He thought it would be nearly impossible to research his family in Europe because many had vanished in the Holocaust, and he assumed no records existed. His interest changed when serendipitously, in 1996, Tom had a conversation with a second cousin on his mother’s side who mentioned he’d been in touch with Tom’s first cousin in Wales. Tom was shocked to know he had a first cousin, much less one in Wales. Alena Morgan née Fischer was the daughter of Tom’s father’s brother. Until that time Tom didn’t even know that his father, Rudolf “Rudla” Fischer, had a brother. When long-distance communication was established Alena told him Rudla had a cousin in sunny Florida whose name was Valdik Holzer. Valdik’s mother, Olga, was a sister to Tom’s grandmother, Karolina. Through this lineage, Tom Weiss and I share great-grandparents, Jakub and Teresia (née Vodickova) Orlík. When Alena described Valdik’s adventures in China, Tom remembered he’d seen photographs of someone in China in his mother’ photo album. When he looked at them, he saw they were marked as Valdik.

When I first heard about this new second cousin who’d arrived on the scene, I was somewhat suspicious. I was thinking about newspaper articles I read in which the story about a long lost relative didn’t turn out so well. My father assured me that Tom was indeed not a con man but my cousin, the son of a person who at that time I had never heard of. Over the next year, through my dad, I was to discover much about the background of Tom’s disappearance during World War II. I was also to learn of Tom’s impressive dedication to uncovering all he could about his past. By the time we met, he’d already traveled to archives in Bad Arolsen, Germany, Vienna, Austria, Ukraine, Poland, and the Czech Republic for his family tree detective work.

His story was another war tale that reminded me of how far-reaching the devastation had been to families worldwide. Well beyond the death camp horrors and the battlefield casualties, for a myriad of reasons innocent families fractured and fell apart. Much of Tom’s experience had echoes of today’s tumultuous world of forcibly displaced persons. Tom’s story, when I met him, was one with heartbreaking residual effects that he was still dealing with. Unraveling the story of his life as a small boy, the adult Tom was trying to understand what and had happened and why.

In May 1999 Tom and his wife, Aurice, met my father in Florida. Tom had already been in contact by telephone for a couple of years. In those conversations he was catching up on what had happened sixty years earlier, when Tom, only four and a half years old, and his parents fled from Prague to Néris-les-Bains, France, saving themselves from the fate of so many other Jewish relatives who stayed behind. I was visiting my mother in her assisted living care home the weekend Tom and Aurice visited my father. Luckily, I had the chance to meet my old-new cousin. Instantly we forged a bond of friendship, sparked by a shared obsession for genealogical research.

Intrigued by my father’s excellent memory, Tom audiotaped his interviews, as I had done a decade earlier. A year later, after my father’s untimely death, Tom shared the tapes with me. Within the conversations were impressions from painful remembrances that I had not heard before, coupled with stories of long-ago happy times. He also sent me the photo of my father that had been in their family album. He said it arrived to his then refugee family living in France sometime between February and April 1940, just before the German invasion of the Low Countries and France. Tom also sent me a massive 2½ x 5–foot scroll of a family tree of the Vodicka branch going back to 1720—research about our great-grandmother Teresia’s ancestry. His hard work was critically helpful as I struggled to identify over three hundred names mentioned in the four hundred letters my father had hidden away.

In turn I shared with Tom the letters written from 1939 and 1941 in Czech between our fathers, detailing what his parents’ lives were like during their exile in France. They were living in a small village, thinking that after fleeing from Nazi-occupied Bohemia, it was a safe haven. That thought was shattered when Germany quickly defeated France. Tom provided me information about how Rudla had joined the Czech army in France, and after the German invasion in April and May 1940 of Denmark, Norway, Belgium, and the Netherlands, Rudla was called up to join the British army. By September 1940, after the fall of France, his father was in England but not with his family.

Unfortunately, for reasons we will never know for sure, Rudla left his wife and son behind in France, and with great difficulty and peril, they made their way south to Marseille. After being refugees in Italy, France, Spain, and Portugal for an adventurous and sometimes harrowing twenty months—most of it in France—Tom’s mother was able to attain entry visas and ship passage to America for her and her son. Nearly destitute, they settled in New York City.

In 1947 Rudla and Erna received a divorce. Upon his mother’s remarriage in New York City to Eugene Weiss, a Hungarian immigrant, Tom became Eugene’s adopted son and took his name. Except for a little correspondence, after his adoption, Tom was estranged from Rudla for the remainder of his life.

In 2008 Alena translated the exchange of letters between Tom and my fathers. Although the letters brought Tom information he didn’t know, such as the exact date in 1939 when his family reached France and an appreciation for the warm affection in our fathers’ relationship, the letters opened old wounds, forcing Tom to relive painful feelings from his childhood. We often communicated, sharing our emotions over what the letters had revealed to us. After reading one translated letter from August 1941, about the mystery of Rudla’s abandonment of his family, Tom commented:

The letter did make me sad. But I have mixed feelings about it. I think he did care deeply for my mother, but I also think he felt guilty about abandoning us in France and leaving us in a very precarious situation. But who knows what anyone would do in such situations?

I am also taken aback at the thought expressed in the letter that my mother did not really need any help. She worked in a sweatshop in New York’s garment district, and I recall she worked five full weekdays and a half-day on Saturday. I would go with her on Saturday since she had no one to take care of me. It was very difficult work and took its toll on her health. She died just before her forty-fourth birthday.

As Tom read German, he became my go-to translator for German documents except for those written in the old German cursive style known as Kurrent. Tom informed me that Hitler had outlawed Kurrent around 1941 because he characterized it as being of Jewish origin.

We both wondered why our fathers let their relationship dissipate after the war. We weren’t even sure if they had ever met again. Long before our modern world’s many available avenues of communication, Tom’s summary described the story of so many broken family bonds after the war: “I think maintaining relations is hard over such large distances and large time separations. Both my father and yours carved out new lives and went their separate ways.” Thankfully, our relationship grew, and Tom and I were given the opportunity to continue the extended family bond when he and Aurice visited Roger and me at our Florida home in 2010.

www.joanieschirm.com Order MY DEAR BOY anywhere books are sold. Or through my publisher, UNL Potomac Books, use code 6AS19 for 40% off.