TIME TO WRITE…Tales from the Writing Journey

Along my now nine-year writing journey, I’ve encountered many incidents that I believe entail a wink from the cosmos. This short story involves a nod from the star character of my books-my dad-prodding me from the great beyond. Let me know if you agree that this sounds like a cosmic wink or feel free to share stories of your cosmic wink tales at joanie@joanieschirm.com

Schwarzenberg Palace, Vienna brass door hanger

The end of 2007 was a reflective time for me. In a month’s time, I was to sell my ownership in the Orlando engineering company I founded seventeen years earlier. Finally, I would transition to a writer’s life. The anticipation was high. So was my anxiety level about this significant life change. To reduce my stress, I tried to concentrate on a string of daily activities. I spent the entire New Year Eve morning on the dismantlement of Christmas decorations for their annual storage in a small, already crowded closet under a stairway.

That morning, my husband Roger’s related job was to pack the decorations in the closet as best he could among other household goods. As he arranged one container box upon another in the bulging space, I heard my husband observe:

“You know you really need to store your mother and grandmother’s antique silver pieces in a better way. Two sharp prongs from the old serving fork are sticking out the side of the bag. Be careful.”

It was apparent when I stored the silver away after a recent family dinner, I’d jammed too many pieces into one of my mom’s two old brown felt bags. Now the fork made known my secret haste. I felt a twinge of guilt to improve the situation, but more importantly, the great Florida outdoors was calling me. I needed to go for my daily exercise walk.

As I’d done each morning for the preceding year in preparation for writing my dad’s story, I grabbed one of my father’s audio tapes to accompany me on the stroll. The tapes were my attempt to recapture stories he’d told endlessly during my youth. I’d forgotten a lot of what was recorded in 1989 and was refreshing my memory to see what I might incorporate into my books.

My neighborhood hikes over old brick streets provided grand opportunities to experience a kind of time-travel back to the mystical places my father talked about. As his voice transported me, I disappeared into another era, and met relatives whose DNA created my features and blood ran through me. The tales let me live through his 1930s and 40s wartime escapades along with accounts from his 1950 and 60s medical practice in Melbourne, Florida where I grew up.

Depending on the tape I was listening to, I could be on a steam-puffing train with armed Japanese soldiers occupying China in 1940 or, the next moment, with a rocket scientist my father knew in the 1960’s, shaping the Nation’s emerging space program in Central Florida. As the pain of the Holocaust kept my dad from telling me much about his parents, stories from his happy childhood gave me a welcome, magical glimpse of what my grandparents Arnošt and Olga were like. I never tired of hearing my father’s Czech-accented voice as my feet walked in Orlando, but my heart traveled all over the world encountering adventure.

Over the previous months of periodic listening to these audio tapes, I tended to dwell on the history of my father’s early years in Bohemia or China. That winter day I felt like hearing something different, so I purposely chose a more contemporary, upbeat storyline period from my old home town. By the title, my dad wrote on the tape, “Melbourne,” I thought it would contain interesting cases from his medical practice.

As I walked the first two blocks, I listened to stories of engaging patients. I got to meet the famous architect Henry Hornbostel who designed the campus that is now Carnegie Mellon University and several iconic New York City bridges. Due to some prior military service, my dad called him “Major” Hornbostel. He apparently wintered in Melbourne Beach where he chose my father as his doctor. Like with so many other patients, they developed a friendship. I also ‘met’ Larry Sheldrick, a retired engine and chassis engineer who was involved in the original design of Ford Motor Company’s Model A. Sheldrick, Ford’s Chief Engineer become a vice president in Detroit with both Ford and General Motors companies. His daughter, Bonnie DeKalb, was one of my mom’s best friends. Next, on the tape, my dad switched briefly to a story about the Space Age that dawned near our home and his physician role to Werner von Braun among others.

Suddenly my father changed subjects. With a switch to a somber tone, I heard my dad say:

“In 1963 we went back to Czechoslovakia for the first time after the war. This was a trip of mixed emotions. My family in Czechoslovakia had vanished during the war. Only the Marik family survived…”

From previous times I’d listened to his recordings, I’d gotten used to my father jumping around with his stories, offering them up in no chronological order. But on that morning promenade I hadn’t expected to amble into this point in his life when he would finally return for a visit to his native land – now dangerously controlled by the Communist Party behind what was known as the “Iron Curtain.” My own mood instantly adjusted as my pace slowed on the uneven bricks beneath my feet.

My dad’s storyline continued in a bittersweet manner with information about the Marik family before and after Nazi occupation ended in 1945. I knew after the Nazis attempted to carry out their “final solution,” the Marik family was among the few remaining Czech relatives stemming from the patriarch Holzer line. Aunt Valerie “Vala” Marik was my grandfather Arnošt’s sister. Miraculously, all four Marik family members – Vala, husband Jaroslav, and sons Jiri and Pavel – survived. They became my dad’s link to his vanished family. He stayed close to Aunt Vala’s family throughout his life, visiting them nine more times after the 1963 trip.

He described how his mother Olga’s silver was buried in an orchard at the Marik’s homestead after the Nazis issued a 1941 proclamation to Czechs to turn over their valuables, such as precious gold and silver. To hide what they had, my grandparents gave their silver and jewelry to Vala and Jaroslav. Uncle Jaroslav made a map based on the tree locations in the orchard beside his sawmill in their Bohemian village of Neveklov. Between two trees he buried the valuables alongside a fine bottle of brandy to open when the war ended.

Soon, the Nazi forces kicked out all the residents of Neveklov and occupied their home, using it as a garrison hospital. Legend has it that the Nazis used the area to practice for their invasion of Belgium. Soon after the Mariks were evicted from their home, Uncle Jaroslav, who wasn’t Jewish, and his oldest son Jiri (George) were sent to different forced labor camps in Germany. After six years of occupation, when the war finally ended for the Czechs in May 1945, the family returned to their home.

The property had been severely trashed, and the orchard mostly cut down for firewood. The map had been rendered useless. Overtime, Jaroslav and his sons dug there and finally recovered the silver collection, but they never found the brandy. As my father said later when telling the story, the brandy was never meant to be found as there could not be a celebration with the lost relatives. At the end of this particular story, my father described how he smuggled the silver out when my parents left Prague by train for Vienna on their way home to America.

My dad followed on with descriptions of the communist government that had taken over in a 1948 coup and its impact on the Marik family and others he knew. As my feet continued to drift along streets lined by large shady oaks tousled with Spanish moss, I listened to fascinating tales from 1963 about my father’s reunion with old friends and classmates from Charles University medical school. Twenty-five years had elapsed since they’d last been together as young adults before the Nazis arrived.

One of these friends was his Charles University professor of chemistry, Dr. Jan Sula. After WWII, Dr. Sula married Helen Krulis-Randa, one of the debutants of their medical school balls. Before the war, Helen’s old noble family had a number of manor houses and castles in south central Bohemia. Her grandfather was a member of one of the 1800’s governments of Emperor Franz Josef of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

In each major province like Bohemia, there was a representative in the government of the Emperor known as a “Home Minister.” Her father was one of these representatives and also President of a stainless steel cartel in Prague. When the Communists came to power after World War II, they picked him up and put him in jail in Prague. The poor man was a very severe diabetic, and of course, the diet he received in prison was not exactly a diabetic diet. They refused to give him his insulin, and he died in the Communist jail. The estates and manor house were nationalized by the Communists. In 1963 when my father and mother arrived, Helen’s mother was living in small, cold water flat in the old part of Prague.

Since my father had known her before the war, Helen wanted my dad and mother to see her while they were in Prague so one afternoon they went for a visit. The visit was a really painful experience for my father. She was of the generation of his parents, and he was once again reminded of all that had been lost. This cultured old woman was living in a one-room apartment, a rather large room with a small kitchen and outside toilet, used by a half dozen people with similar apartments on the floor.

Helen’s mother had furnished her apartment with some of the most beautiful antiques that came from their old castles, somehow miraculously saved through the war. There were three large wardrobes in this vast sprawling room which she used as room dividers to separate space. In this manner, she had laid out a living room and bedroom. She still had a collection of beautiful antique porcelain and gorgeous Renaissance paintings hanging on the dingy walls.

When my parents told Mrs. Krulis-Randa that they were going to Vienna after their visit to Prague, she asked my father whether he would take a letter to Vienna for her friend, Duke Schwarzenberg, still living at the Schwarzenberg Palace which originally had opened in 1725. As it happened, one wing of this grand old palace was made into a hotel, and my parents had previously reserved a room for their future stay in Vienna. They agreed to the mission of mercy. The day before they left Prague, Helen Sula delivered to my parent’s hotel the letter from her mother for the Duke Schwarzenberg.

After my father had described on the tape that he’d agreed to deliver the message, he went on to tell several other stories about their train trip from Prague to Vienna. I anxiously listened on, wanting to know if the letter made it to the Duke. At last, he described their arrival in Vienna at the Schwarzenberg Palace.

“I asked at the reception desk where I could see the Duke Schwarzenberg. They looked at me kind of suspiciously. Finally, someone said, “Why do you want to see the Duke?” I said that I had a letter for him. Arrangements were made for the following day to go to see the Duke. I was informed that I should wear a dark suit when I went to see the Duke. Ordinarily, I go around Europe in flannel slacks and sports jacket, but I always carry some better suits so we can go to the opera or something like that. I got all dressed up, shined my shoes, and went for the appointment.

At the entrance to the palace, I was met by a footman in the proper uniform. He led me upstairs to the second floor where I was met by the Duke’s secretary who was a middle aged gentleman in a dark cutaway suit. He instructed me how to behave on my entrance to the Duke’s study. I was supposed to enter and walk to the desk where he was sitting. I should stand up behind the desk but not to say anything until the Duke addressed me. I followed his instructions, but as soon as I entered the room, the Duke got up, walked toward me and shook my hand. Then he took me to his desk and asked me to sit down. I handed him the letter which he immediately opened and started to read. He stared making all kinds of comments in German. Then he turned to me and started talking in perfect Oxford English. He asked me how things were in Prague, whether I met his cousin. When I told him I got the letter through Mrs. Krulis-Randa, he said, “Well, how is the old girl?” After a short conversation, he said, “I detect some accent in your English. Do you speak German?” I said “yes” and from then on we conversed in German. I stayed there for about ten minutes. Then we got up and he walked with me to the door and shook hands again.”

Obviously recalling this exchange with great pleasure, my father closed with:

“And so that is how I ended my audience with the Duke Schwarzenberg.”

As often happened when I listened to the tapes, I walked home feeling as if I’d had a fine morning meeting with my late father. Although some of our time together included sad aspects, most of it made me joyful for what life entails – extraordinary and ordinary happenings of life.

When I returned home, I decided to take some constructive action to store my Mother’s silver pieces in a more deserving manner. I pulled the brown felt bags from the closet and laid them on the dining room table, carefully removing each silver piece. I enjoyed thinking about how some of these were my Grandmother Olga’s secretly buried silver pieces. Somehow they went undiscovered by the rotten Nazi’s as they carried out shooting practice unknowingly standing atop them; a small piece of justice in a world mad with injustice.

It was customary for my Mother in the 1950s to carefully wrap her silver pieces with white tissue paper. It was believed then that the tissue would protect it from tarnishing. Upon my inheritance of this share of family heirlooms, I couldn’t bring myself to dispose of the tissues my mother chose to protect them. So the paper remained in place. Within the two felt bags were various items I’d never used – like old silver cigarette lighters and small sugar plates. It had been a long time since I polished anything in the bags. I decided it was time to remove all the belongings and reverse their tarnished condition.

As I laid them on our dining room table, I came across something I hadn’t noticed before. In a thicker-then-usual piece of white paper was something brass, not silver. As I removed it, I held what appeared to be an old doorknocker. On the front top half, carved in great detail, was a man riding a horse. The horse and his rider were perched atop an emblem of sorts which had the number “8” engraved on it. Holding it in my hands rubbing its beautiful brass, I found myself smirking. Apparently, at some time in his extensive world travels, my father must have “lifted” this doorknocker. It seemed uncharacteristic for him and definitely was not my mother’s style. Staring at the doorknocker for a long minute, I wondered how the item made it into the silver collection.

And then it happened. I turned the doorknocker around to look at its backside and there, etched in the brass in black letters was:

Hotel Palais

Schwarzenberg

I loudly gasped, and my body shook.

Sitting nearby, my husband asked what happened. I described the story I’d just listened to on tape and what I now held in my trembling hands.

Roger smiled as he calmly replied. “That is clearly your father telling you that you need to get busy writing his stories.”

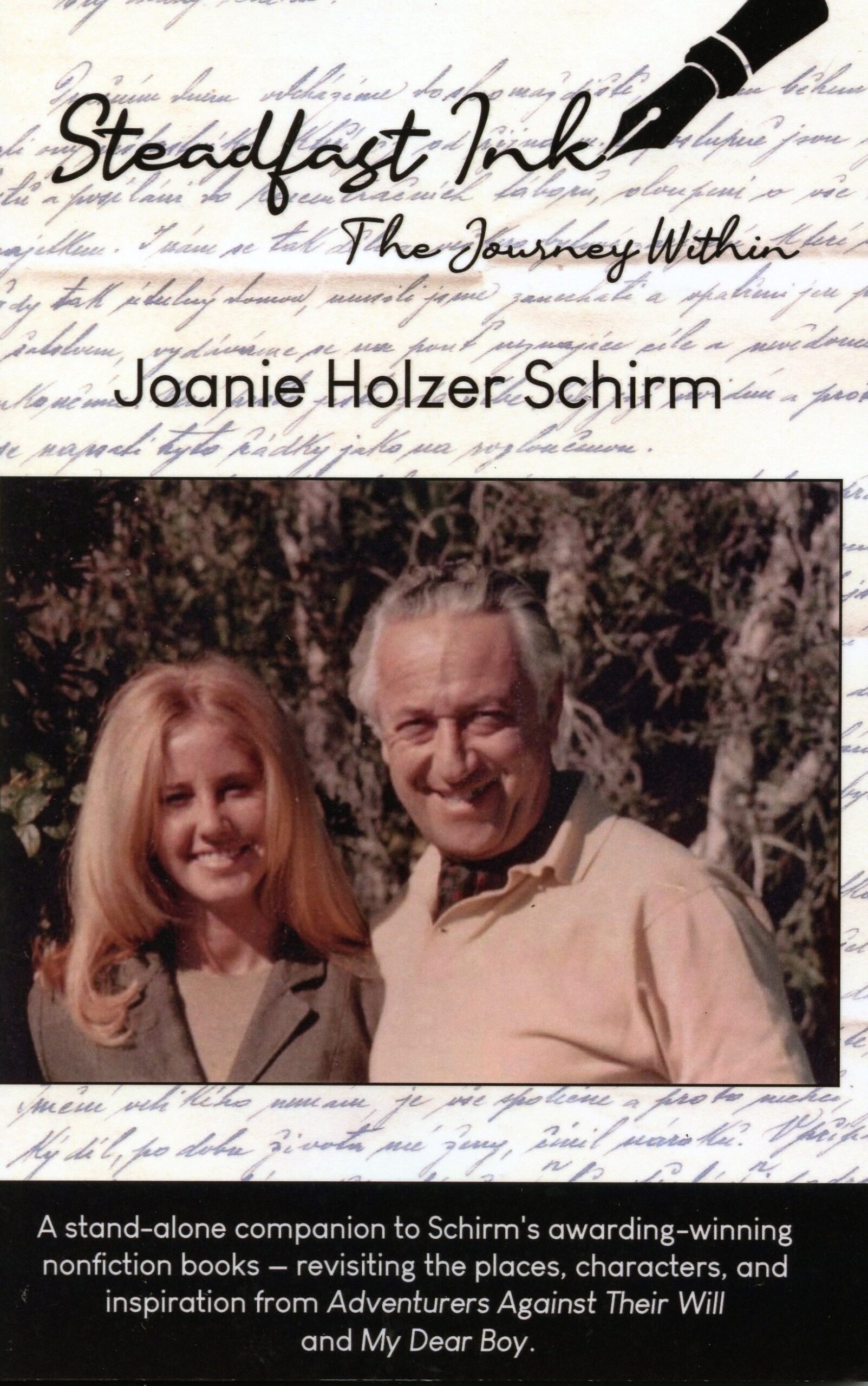

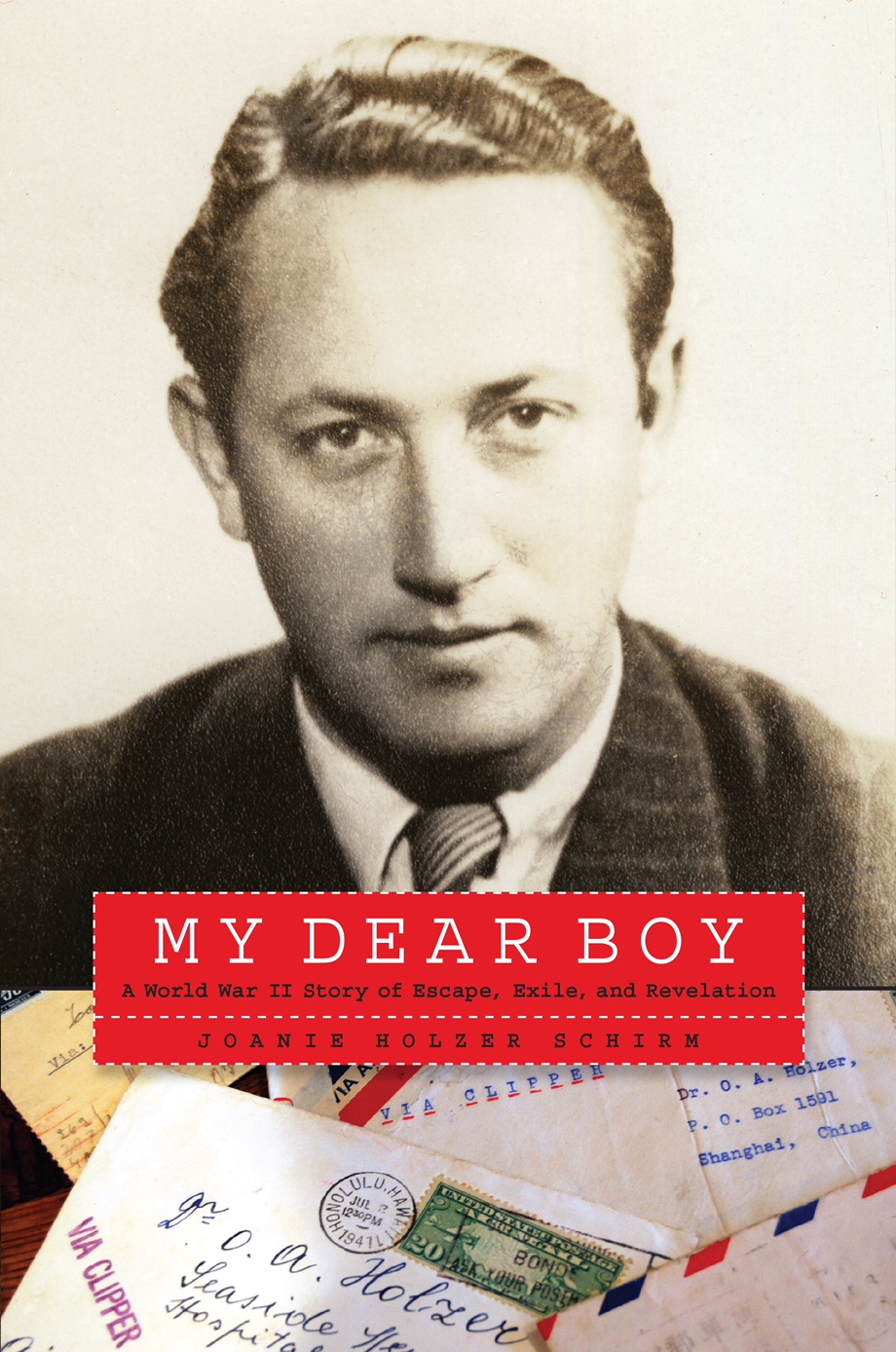

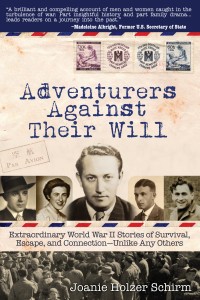

{Wish granted: 2013 – Adventurers Against Their Will published and won the 2013 Global Ebook Award for Best Biography; 2017 finished manuscript for My Dear Boy (not yet published); two more related books underway in my writing room}