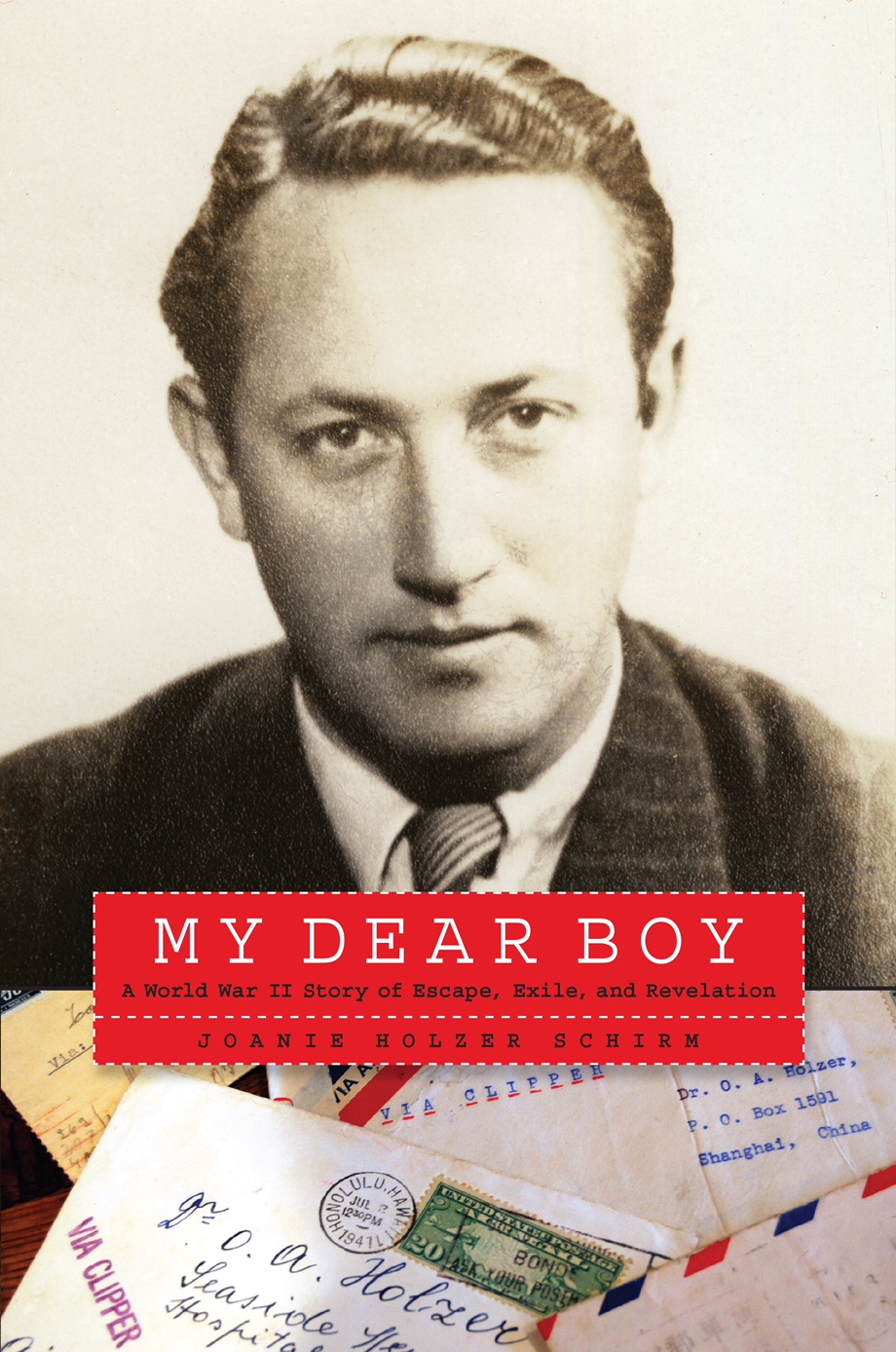

Seventy-four years ago, Oswald “Valdik” Holzer started a trip that never ended. Beginning a twisted worldwide journey, on May 21, 1939 my father forever departed from his homeland; only to return “home” again as a visitor. As he left, he said goodbye to his parent’s at Prague’s Woodrow Wilson train station. Two months earlier, his beloved city had become part of what the Nazis called their occupied territory: the “Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.”

As a young, Jewish physician, Valdik was seeking safe harbor away from growing persecution. His beloved parents chose to stay behind. At the station, they wished their only child a safe journey of 8,000 miles through three continents to his destination of Shanghai. Valdik had no idea it would be the last time he saw his parents. Arnost and Olga Holzer would become victims of the Holocaust, likely perishing in eastern Poland at the death camp named Sobibor.

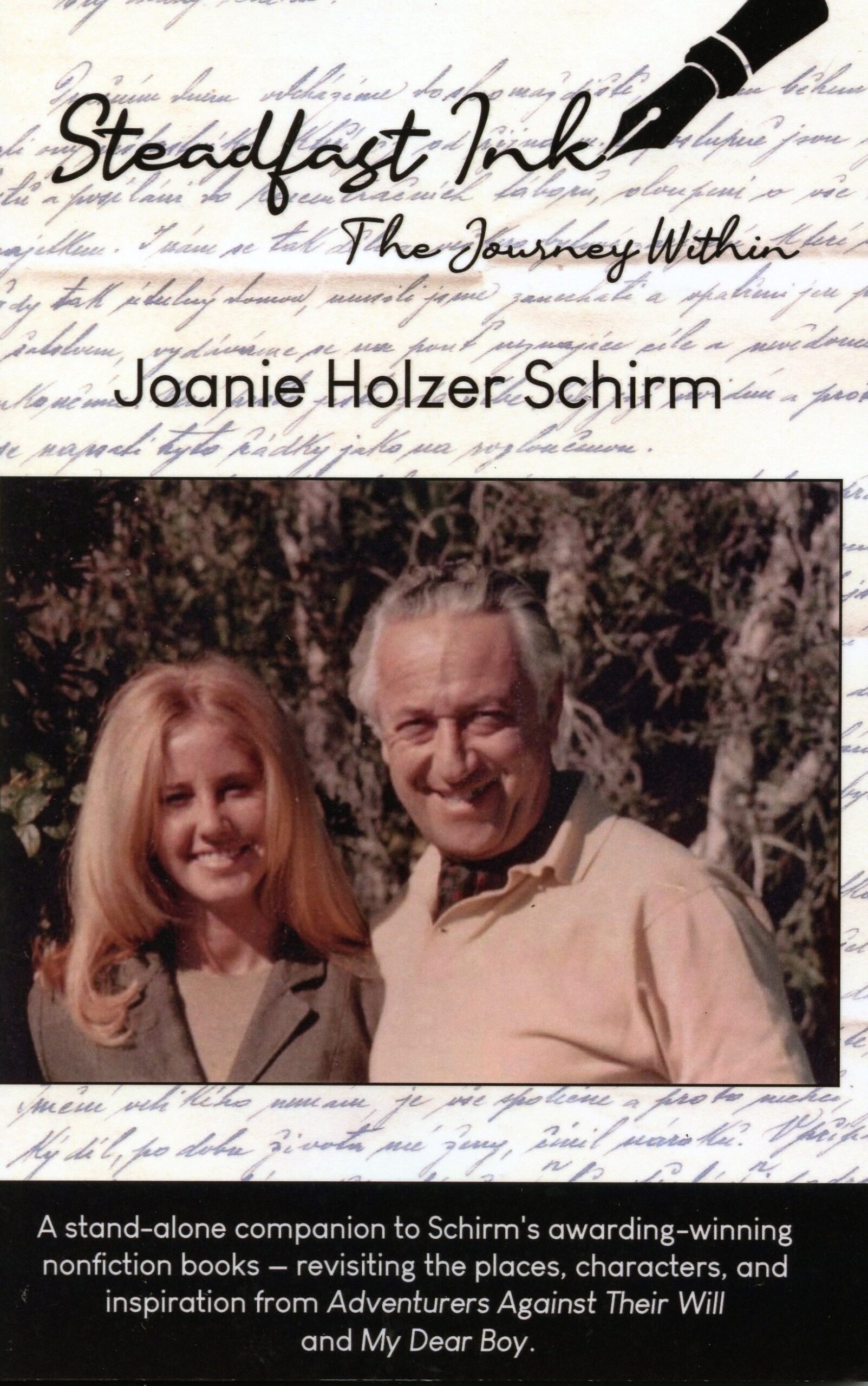

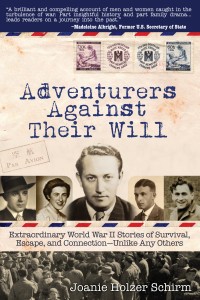

Upon my father’s death in January 2000, a discovery was made of 400 letters by seventy-eight Czechoslovak writers who reached my father with their words as he ultimately traveled during WWII through five continents. Ultimately he settled in Florida in 1948 where he hid the letters away in red lacquer Chinese boxes. The letters form the basis of my debut non-fiction book: Adventurers Against Their Will. The story centers on seven of the letter writers and my modern day quest to find them and complete their stories. Through their far-reaching personal histories, I listened as the past became prologue and revealed meaningful lessons for humanity.

What follows is an excerpt from Chapter 1, Voices of the Past about that life changing moment:

…For me, Dad’s storytelling was as essential as oxygen. The images he painted with words were so tangible; I could almost taste Czech roast pork with dumplings and sauerkraut. He expressed his joie de vivre, filled with adventure, a passion for justice, and sincere affection for family and friends. I could never get enough of the eloquent memories of his escapades, the people he met, or the places he traveled.

My father’s rugged, exciting Bohemian youth was a world apart from my idyllic childhood of sunny days and warm, rolling surf on a barrier island in Florida. I loved the mystery he created as he trailed off midstream, as if floating into some sort of trance. His deep, slightly accented voice would eventually resume near where he had left off and flow into another story, creating a tangle of tales like the wavy black curls on his head.

It was many years before I came to understand that those tantalizing drifts and pauses weren’t merely for dramatic effect—my father was editing his life.

He did this so skillfully that I grew up believing I knew far more about him than I actually did. I knew he was Jewish in a time and place where that could have had tragic consequences. I knew his parents suffered those consequences when they perished in the Holocaust. I knew he escaped the same fate by fleeing to China, where he found my mother and happiness, only to flee once again as World War II closed in around them. I knew about my parents’ lives in Florida, and my father’s career as a compassionate doctor. Most of all, I knew we were different, and I loved that. Who else had a dad who fled the Nazis, or a mother who spoke Chinese?

But he’d never told me the whole story. I knew my father had been serving in the Czechoslovakian Army when the Germans invaded in March 1939. Overwhelmed, his country surrendered. My father slipped away from his unit and boarded a train for Prague. He made plans to emigrate, and his medical degree became his passport to a brighter future. He’d worked for the Bata Shoe Company’s medical department three summers before and was able to use his connections there to arrange for a document stating he was taking a new job in the company’s branch in China. The Germans were quick to clamp down on Czech flight, so the Bata employment papers were important for Gestapo clearance. In my father’s telling, this was a stroke of good fortune that would allow him to establish himself in China and eventually send for his parents if they decided to join him.

But after reading a letter my father wrote on February 7, 1940, to a Czech neighbor, Dr. Veselý, I realized Dad had never intended to go to China.

…As you know I left Prague in May and got to Marseilles, where I boarded a ship for China. I totally did not intend to reach the destination, I wanted to stay somewhere along the journey. Disregarding the fact I had no visa, money, etc. It was damn difficult as I did not even know well any world language, except for German.

What started out for my father as a destination to satisfy the Nazi bureaucracy became the best and probably only choice, so he embraced it—motivated by his spirit of adventure and his youthful sense of fun, despite all the sorrows that were unfolding in his world. The more I understood, the more I tried to piece together. I matched details from one letter to another and then cross-checked them with other sources. The effect was overwhelming. The letters were full of beauty, adventure, and joy, but also loneliness, confusion, and grief. It was a rugged world for me to live in day after day, and I began to fear that the project of organizing, translating, and preserving the letters was more than I could handle. But I was propelled forward by a powerful sense of obligation to my father, who surely knew I would find the letters, as well as to the people whose lives and struggles they detailed. I realized this was a larger, more powerful story than I’d anticipated. I also realized these letter writers were only telling incomplete tales and there was much more to uncover.

My father never told me about the close friends he lost to the horrors of war, or the others who suffered gravely in concentration or forced labor camps, or simply from the effects of the ruthless Nazi rule of their homeland. Forty-four relatives perished in the Holocaust. Displaced by the Nazis, Dad and his friends who survived suffered from guilt for the rest of their lives, either because they escaped and others didn’t or from a sense that they could have done more. Some buried their guilt deeper than others, yet in the end, most displayed the indefatigable Czech resilience. They went on to rebuild lives, bringing a haunted peace and fulfillment to themselves and those they loved.

Through the letters and my research, I became a part of these friendships, many begun at the Mánes Café in Prague during the First Republic of Czechoslovakia’s glory days after the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s collapse and before the arrival of the Nazis in 1939. Most of us remember gathering places from our own pasts that represent the brave and hopeful moments of youth and future, and Mánes was that place for Prague’s creative young people before the war. It was such an important and profoundly influential part of the lives of my father and his friends that it became essential to understanding who they were and who they became.

www.joanieschirm.local