October 2016

It’s always important to use history as a guide. If we can learn from the past, we might have a chance to avoid future catastrophes.

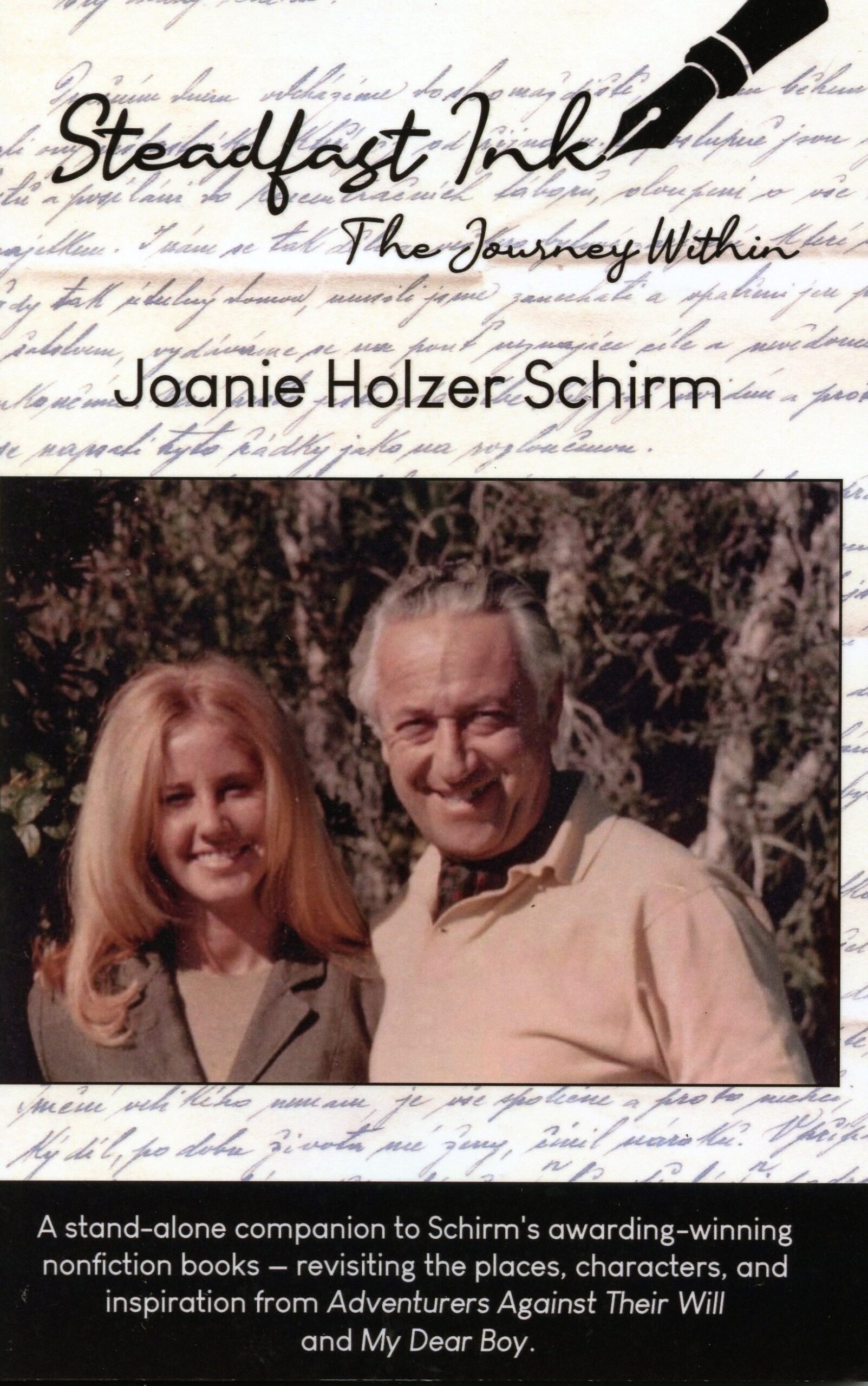

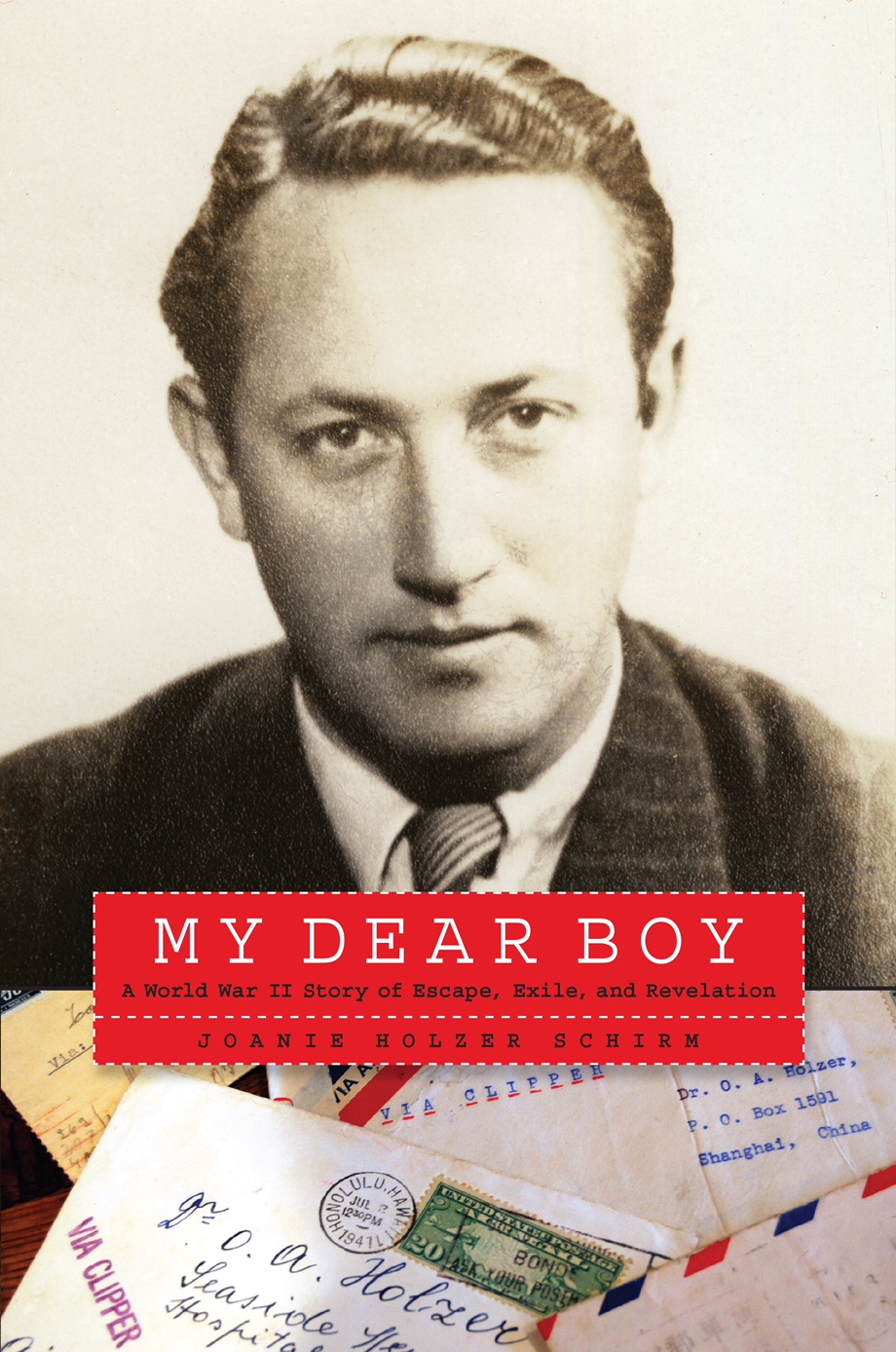

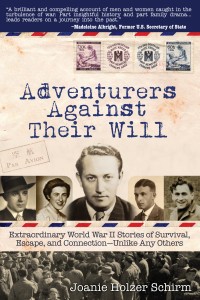

The following excerpt is from my upcoming book, My Dear Boy, the detailed story of my Czech-American father’s life before, during and just after WWII. The passage depicts days following the signing of the Munich Pact on September 30, 1938, by Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, French Premier Edouard Daladier, and British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. In the purported name of peace, the agreement gave Hitler the Sudetenland, a part of Czechoslovakia where 3 million ethnic Germans lived. The pact also delivered without a struggle to the German war machine over 60 percent of Czechoslovakia’s coal, iron and steel and electrical power. Weakening Czechoslovakia and its borders beyond repair, it gave the Nazis needed resources to in March 1939 occupy the remaining Czech lands and in September 1939, begin WWII with the invasion of Poland. This section of the book briefly describes my father’s plight as a Czechoslovak Army soldier ordered to ‘observe’ the turnover of an important piece of his country after his homeland had no say in the agreement.

…he thought about the world leaders who’d signed the Munich dictate. They apparently knew who and what they were dealing with. Years before Adolf Hitler became the German chancellor, in countless speeches he’d espoused his beliefs of racial “purity” in what he called an Aryan “master race.” Even while Dad had drawn his Adolf-like caricature just as he was, not unusually tall with brown hair, Adolf let the world know the supposed superior physical traits of the Aryan or Nordic type and inferior characteristics of the non-white and Slavic peoples. The nature of this man’s character should have been a warning to the world. In the meantime, Dad’s small Czechoslovak Army force got new orders.

His regiment was ordered to retreat and surrender the Sudetenland to the Germans while helping to supervise their evacuation. It took less than three weeks for the occupation forces to assume their positions and incorporate the region into Germany. It was a strange and sickening feeling to realize the land he was standing on—the land he’d been sworn to defend—had become German soil as a result of some paper signed by the leaders of other countries. It was, even more, disturbing to discover they had no leader of their own. Five days after the betrayal at Munich, President Beneš resigned and fled the country, accepting an invitation to lecture at the University of Chicago. Middle Europe was once again in flux and reflecting a familiar inevitability of Czech sovereignty in danger. The vultures had successfully created their opportunity and were circling overhead. As a Slavic man fitting the Nuremberg definition of Jew, Dad saw himself as a double target—a helpless prey of some poisonous animal.

When he arrived in Sudetenland with his troops to observe the turnover of their land to the Germans, he watched German soldiers cross the old Czechoslovak border (near Grulich, today’s Kraliky). They arrived as motorized infantry and cyclists beside what appeared to him as the entire three million or so ethnic Germans living there. Cheering loudly, the locals were already waving the German flag. He knew the loss of their defenses, as well as the industrial strength that was located in that area, was a brutal blow to his nation’s security.

In ominous silence, his unit packed their gear and watched the Germans move into their bunkers. What remained of their country was re-formed into the Czecho-Slovak Republic, consisting of Moravia and Bohemia in the west, Slovakia at the center, and Subcarpathian Ruthenia bordering the Ukraine to the east. The peaceful transfer of the Sudetenland proved to be a cruel fiction as the Nazis set off a wave of violence against anyone who opposed their plan to Germanize the entire territory. In retreat, along with Dad’s demoralized fellow soldiers, he observed many Czechoslovak citizens become homeless refugees. Through the bitter cold on windswept roads, they traveled with just a few belongings on their carts.